Water voles, one of Britain’s most endangered mammals, have been sighted in the River Thame catchment for the first time in almost two decades, offering fresh hope for conservation efforts in Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. Volunteers with the River Thame Conservation Trust (RTCT) captured video evidence at two sites using motion-sensor cameras, confirming active individuals despite a national population crash exceeding 90% since the 1990s. The discoveries, near Chearsley and Stadhampton, highlight improving river health after years of restoration work targeting habitat loss and invasive predators.

Dramatic Sightings Confirm Presence

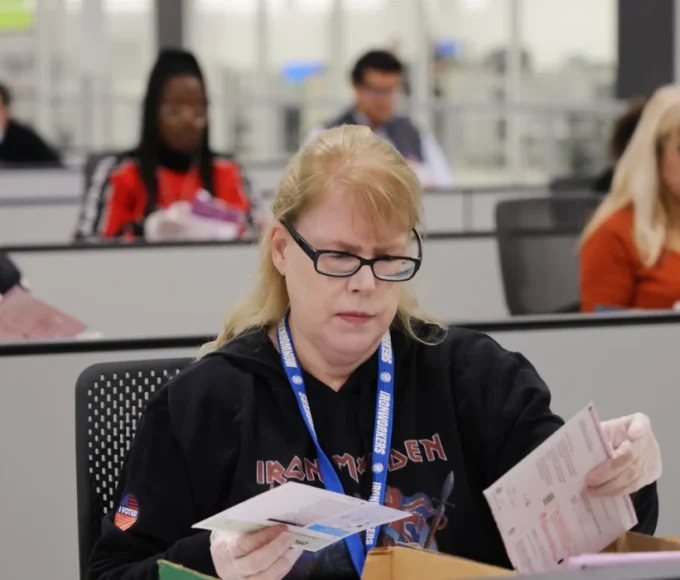

Clear footage emerged from RTCT’s ongoing monitoring program, which deploys wildlife cameras and mink-monitoring rafts across the catchment, sifted through by dedicated volunteers reviewing thousands of clips. At Chearsley on the River Thame, a striking sequence showed a heron preying on two water voles in succession, a harsh but definitive proof of their survival. Separately, on Chalgrove Brook near Stadhampton, another camera recorded a vole swimming away from a raft, indicating at least one healthy specimen in the area.

These mark the first verified records since the early 2000s, when local populations were already dwindling rapidly. Volunteer Paul Jeffery, RTCT treasurer and Oxon Mammal Group member, spotted the initial clue after scanning about 1,000 clips: the animal’s blunt face, distinct ear and eye placement ruled out common rats. Cameras at these sites routinely detect rats, mice, and otters, signaling a rebounding ecosystem.

Decline Drivers and Conservation History

Water voles have vanished from 94% of their former UK sites, driven by habitat destruction, water pollution, and predation by non-native American mink. In the River Thame, they were deemed functionally extinct until these breakthroughs, despite intensive surveys. A 2006 reintroduction at Cuddington and Ickford released voles into primed habitats, but follow-ups over three years found no lasting evidence, with mink likely responsible.

Origins of the current voles remain uncertain: they could descend from that project or from undetected native holdouts, given the distance from release points. The heron predation, while sobering, underscores a revitalized food web, with voles as prey supporting top predators—a hallmark of balanced riverine environments. As indicator species, their needs for clean water, stable banks, and lush vegetation reflect broader floodplain health.

Volunteer and Expert Reactions

Paul Jeffery expressed optimism: the find offers “genuine hope that water voles are still hanging on and may one day recolonise the whole river system with our help.” RTCT’s Hilary Phillips hailed it as “a fantastic affirmation of all the hard work by volunteers and landowners,” proving “our combined efforts are making a difference.” She noted small regional populations persist and stressed sustaining habitat improvements and mink control to prevent further losses, “igniting hope” for full recovery.

Conservation partners like Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust (BBOWT) and water vole specialist Dr. Merryl Gelling contributed to the monitoring success. Phillips urged public reporting of sightings or mink via tools like INNS Mapper to map distributions and aid recolonization.

National Recovery Context

The River Thame milestone aligns with UK-wide initiatives reversing water vole fortunes. Projects on rivers like the Colne, Wey, and Hogsmill, plus Broads reintroductions, show promise where management persists. A 2025 national report detailed losses but optimism from targeted actions, including Surrey releases and talks on beaver-vole synergies.

BBOWT’s long-term recovery efforts emphasize sustained intervention. Thames sightings build on this, with RTCT crediting farmer-landowner collaborations for habitat gains. Continued vigilance against mink—via rafts and traps—remains pivotal for population stability.

Monitoring’s Role in Success

RTCT’s camera network exemplifies citizen science: volunteers process vast footage, identifying rare events amid common captures. This low-cost, high-impact approach has uncovered hidden resilience, informing adaptive strategies.

Implications for River Restoration

These vole returns validate Thame restoration investments, from bank stabilization to pollution curbs, fostering conditions for keystone species. Ecologists view them as harbingers of trophic recovery, where prey abundance sustains predators like herons and otters. Broader benefits include enhanced biodiversity, flood resilience, and community engagement through volunteering.

Challenges persist: mink proliferation and climate pressures demand ongoing commitment. Yet, with 20-year absences bridged, the Thame exemplifies how localized action can revive national icons. Public involvement via sightings reports could accelerate mapping, targeting reintroductions or protections.

As 2025 national data underscores uneven progress, Thames successes inspire scaling: similar monitoring elsewhere might reveal more “ghost” populations. Conservationists call for policy support, blending mink eradication with habitat funds, to secure water voles’ foothold amid environmental flux.