While countries engage in concerted science diplomacy, Canada’s efforts are haphazard and irregular.

Since Galileo (an Italian) was inspired by the work of Copernicus (a Pole) in the 17th century to promote the heliocentric model of the solar system – much to the dismay of the Pope! –, international collaboration is a characteristic of scientific research.

Four centuries later, governments began to get involved in international scientific collaboration to support and promote such interactions. It is notable, for example, that the National Research Council of Canada was established in 1916 to promote scientific and industrial research in collaboration with the United Kingdom, to support the war effort.

However, it is only in recent years that the idea of scientific diplomacy led by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has emerged. In this contemporary context, Canada has fallen behind.

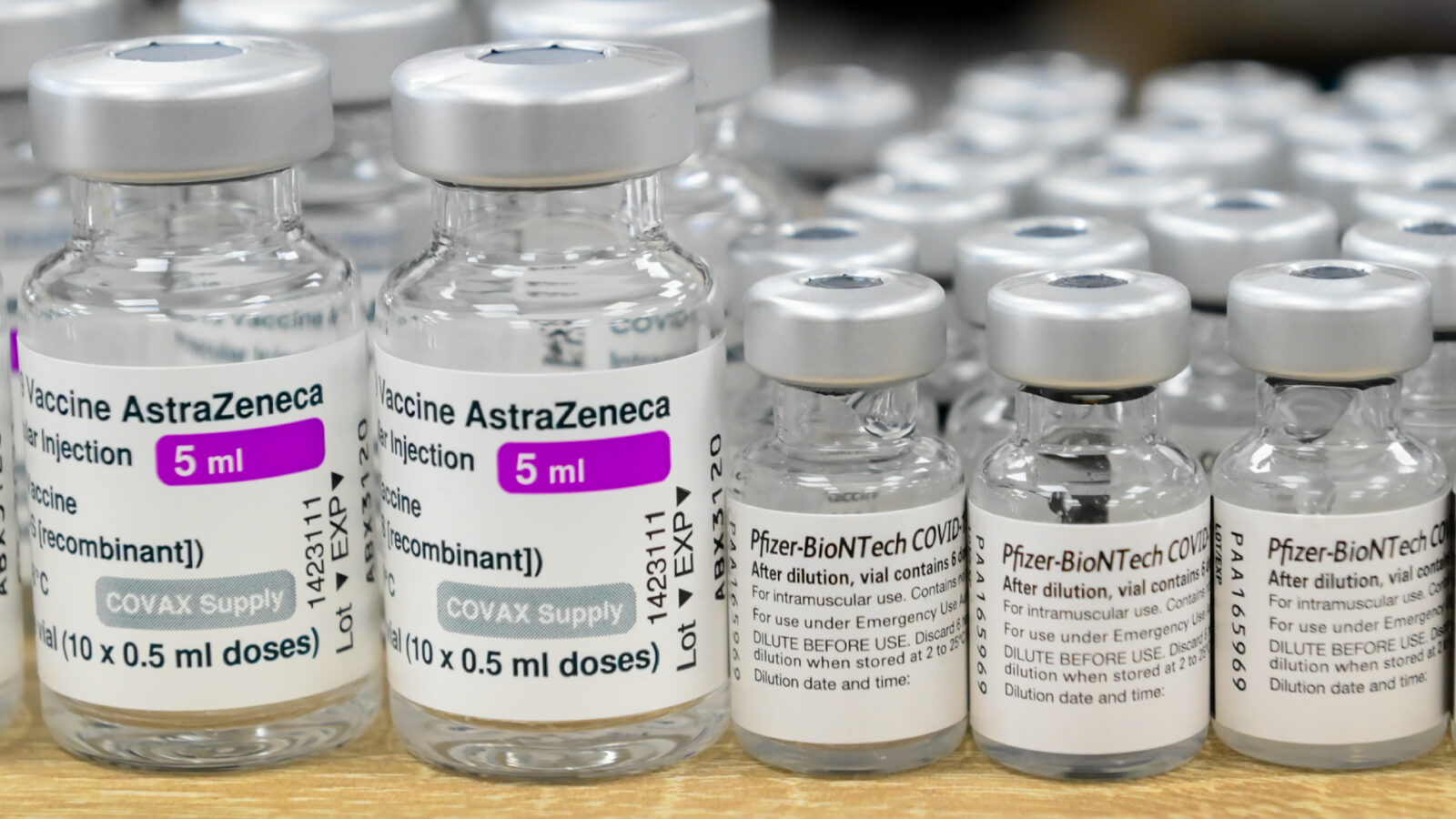

Whether it was science in the service of diplomacy or diplomacy in the service of science, this relationship remained relatively discreet until the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Governments responded out of the need to facilitate international scientific collaboration, in order to develop vaccines as quickly as possible (in this case, in a single year, instead of the usual 8 to 10 years).

The pandemic has also raised awareness among political and diplomatic leaders of the need for timely, accurate and informative scientific data that can only be developed and shared quickly and widely through collaboration that crosses borders.

Clearly, science diplomacy can play a role in international relations.

The American and European advance

In the United States, science diplomacy has its own office in the White House, and it is managed by the Department of State (the US Department of International Affairs). For its part, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the world’s largest scientific society (and publisher of Science magazine), hosts the Center for Science Diplomacy to help integrate scientific collaboration efforts international contribution to the State Department’s diplomatic efforts.

Likewise, the European Union has made extensive efforts over the past five years to put in place a strategic framework that ensures that national and continental research and innovation efforts support the EU’s diplomatic interests and are consistent with these. These same efforts in turn aim to ensure that diplomatic efforts support the research community and that decisions are based on science and expertise.

Meanwhile, Canada’s many scientific institutions, including universities, research foundations and national and provincial scientific research agencies, are actively collaborating with international partners. But they do so with little or no support or coordination from Global Affairs Canada.

False start for Canada

In 2020, Global Affairs Canada sought to develop a strategic approach for its disparate science diplomacy efforts. However, this initiative was quickly downgraded to a less ambitious policy development document.

The end result was a guidance document. But rather than defining a strategic approach to deploying science diplomacy, he presented an examination of who, within the Government of Canada, leads international scientific collaborations.

This type of directive encourages the parties to talk to each other in order to find out what other representatives of the Canadian government are doing on the international scene. However, when compared with what the United States and the European Union have put in place or with what was initially intended, the end result is little more than a glorified Post-it.

One reason for this failure, as I have argued, is that Global Affairs Canada generally views science diplomacy as a function of commercial diplomacy.

A more strategic and comprehensive examination of scientific diplomacy would rather place it at the crossroads of cultural, commercial and development diplomacies.

In other words, the strategic integration of international scientific collaboration into existing cultural diplomacy would strengthen Canada’s global influence.

Helping others develop

Although science diplomacy with developing countries will not necessarily result in significant direct research advances for Canada, it could nonetheless be of inestimable value to countries with nascent scientific capabilities. After all, Canadian aid should primarily support the economic, social, political and scientific progress of developing countries, including the achievement of point 17 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

Such a strategic approach would require Global Affairs Canada to develop leadership across its three main functional activities: political and cultural, commercial and economic, and development.

Unfortunately, the internal culture of the ministry is very resistant to such collaboration between its different components.

The three sectors are stubbornly compartmentalized and many employees of the former Canadian International Development Agency still seem bitter about their forced marriage with the former Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (mainly due to a loss of independence and nostalgia for an idealized past, felt by long-time CIDA employees).

For such multidisciplinary collaboration in science diplomacy to actually take place and be effective – and not just to inform colleagues about what you are doing – senior management at Global Affairs Canada must be sensitive to the growing and highly consequential importance of scientific diplomacy.

Ultimately, taking a more structured and strategic approach goes well beyond Canadian research and its role in the world. It is about providing an effective platform for Canada’s broader interests in an increasingly busy and competitive international arena.

This article is originally published on policyoptions.irpp.org