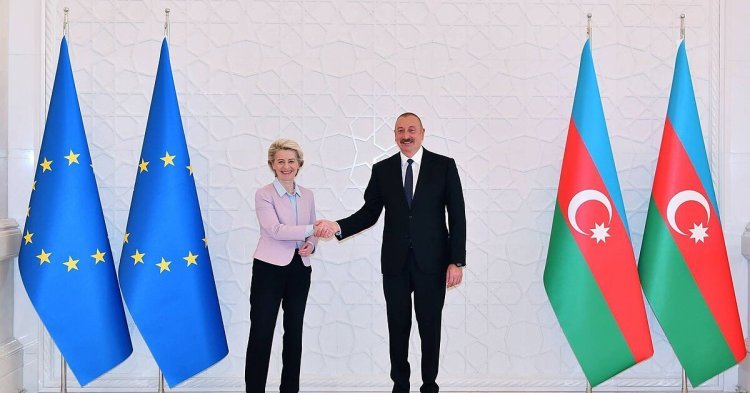

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the European Union (EU) sought to diversify its sources of gas supply to reduce its energy dependence on Russia. It is in this context that it signed an agreement with Azerbaijan in 2022, leading to a significant increase in Azeri gas exports to Europe. Faced with the return of the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, the weak reaction of a European Union keen not to alienate Baku has been widely criticized.

Tuesday September 19, 2023, Azerbaijan launches a new military offensive in the enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh, a secessionist region mainly populated by Armenians, which Baku and Yerevan have been fighting over for several decades. Claiming to be carrying out an “anti-terrorist” operation against the pro-Armenian forces which control it, Azerbaijan was, in turn, accused by Armenia of carrying out “ethnic cleansing”. The following day, as the attack brought back bloody memories of the 2020 war, a ceasefire was negotiated between the belligerent forces. Providing for “the withdrawal of the remaining units and military personnel of the armed forces of Armenia”, as well as their “dissolution” and “complete disarmament”, the agreement allows us to glimpse a peaceful settlement of the conflict, even if the salvation of the Armenian population in Nagorno-Karabakh remains unresolved.

A European Union in retreat

If the Armenian separatist forces agreed on Thursday to consider “reintegration” into Azerbaijan of this disputed territory, the possible resolution through negotiation of the conflict is far from being the work of European diplomacy. Indeed, since the resumption of hostilities, the European Union has contented itself with symbolically condemning the attack, without taking concrete coercive measures. However, Armenia and Azerbaijan are an integral part of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), the very essence of which is to offer the peripheral countries of the EU the conditions necessary for their political and security stability. Its other objective is to “promote the essential interests of the EU in terms of good governance, democracy, the rule of law and human rights”. It therefore seems that the EU is incapable of translating its political ambitions into concrete actions in the Caucasus. The inexistence of European diplomacy in the Nagorno-Karabakh issue – and more broadly the chronic inability of the Union to defuse this decades-old conflict – has led to harsh criticism of it. On Wednesday, in the European Parliament, many MEPs of all political stripes were outraged: François-Xavier Bellamy, French vice-president of the Republican Party, notably warned that “if Europe [remained] passive in the face of the war launched by Azerbaijan against the Armenians of Nagorno-Karabakh, it [would be] guilty before history.”

But then how can we explain the reluctance of the European Union to become more involved in a conflict taking place on its doorstep? How can we understand his laxity in the face of a dictatorial political regime known for its tendency toward warmongering?

The fault of energy imperatives

In the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, political Europe sought to create new energy supply channels, to emancipate itself from Russian tutelage. Deprived of gas from the Kremlin, the Europeans therefore decided to turn to Azerbaijan to keep their heads above water. In July 2022, they signed the agreement which would lead, between 2021 and 2022, to an increase of almost 30% in Azeri gas exports to Europe. In short, if the European Union is reluctant to oppose Baku’s policy in Nagorno-Karabakh, it is because it cannot, let us put it colloquially, “bite the hand that feeds it”. According to Nerses Kopalyan, professor of political science at the University of Nevada in Las Vegas, the fact that Europe has “found nothing better than to go begging from Azerbaijan” explains the European unease which surrounding the resumption of hostilities in Nagorno-Karabakh.

But there was no need to wait for the return of the conflict to see the agreement arouse controversy: the day after its signature, in a column in Le Monde, more than fifty elected officials from all political stripes took the floor to denounce the harmful consequences that would have agreement on the international situation. They denounced the risks of a new energy dependence – arguing that “by choosing Azerbaijan as a gas supplier, Ursula von der Leyen [had] weakened the European Union” – but also of the financing of a regime “which engages in every possible and imaginable human rights abuse.” For them, the contract only shifted the problem of energy dependence and risked strengthening a regime which has not hesitated in the past to use phosphorus bombs, which are completely illegal.

What future for European diplomacy?

Baku plans to double its deliveries to Europe by 2027. According to The Economist magazine, the promise is untenable, firstly because it believes that Azerbaijan will be unable to keep up with demand. growing locally and internationally, but also because doubling its exports will require colossal investments: with the Trans Adriatic Pipeline already running at full capacity, another one would have to be built. If the agreement is therefore politically questionable, it is just as questionable economically. Still, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliev currently has nothing to be worried about; according to Dominique Baillard, journalist at RFI, he can “count on the support of his clients and allies” such as Hungary and the ‘Italy.

Beyond the conflict in the Caucasus, this episode reminds us how difficult it is for the European Union to act as a coherent political actor on an international scale. Dependent on other states for energy supplies, its international diplomacy suffers the consequences. It often struggles to free itself from economic dictates, at the expense of the political and normative considerations that it claims to defend. If the European Union now wishes to demonstrate true “strategic autonomy” in political and security matters, it is clear that it does not yet have the means. The various European strategic redeployment projects, notably the development of lithium mines on the Old Continent, aim to reverse the trend. Only the future will tell us whether these policies will really have an impact.

This article is originally published on taurillon.org